Minneapolis has the kind of traits that make American cities great: a diverse, hardworking community that inspires builders and entrepreneurs; sprawling urban parks and trails that breed a love of the outdoors; and an unpretentious vibe that encourages exciting arts, bars, restaurants, and craft breweries. Robust social services complement a thriving philanthropic infrastructure. But the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police highlighted deep fractures beneath the city’s progressive surface. Protests, rage, fear, and flames devastated certain neighborhoods, igniting a reckoning on race and equality that leapt first state, then national borders. The city itself sustained an estimated $500 million in property damage, all amidst a surging pandemic. For a handful of men in unexpected corners of the city, the debilitating despair required action. An outdoorsman, chef, NHL player, and distiller might seem like unlikely agents of change. But in the darkest hours of upheaval, they saw the need for something new as an opportunity to build something better. These four men prove that it’s not the what that makes America’s cities great, it’s the who.

Anthony Taylor

Leading the Way to Better Outcomes Outdoors in Minneapolis

When I arrive for the Slow Roll bicycle ride, people are already gathered in a parking lot next to a small white house along the tree-lined blocks south of downtown. DJ Walter “Q-Bear” Banks of KMOJ is playing Earth, Wind & Fire. The vibe is relaxed, with 40 or so riders gathering: women, men, boys, girls, mostly Black. It’s an eclectic mix—hipsters, cool kids, bohemians, nerds, a city councilwoman, and the chair of the Minneapolis Board of Education. The youngest rider is 9 years old; the oldest is 79. Some appear to be serious cyclists—light bikes, high-end gear, lots of miles behind them—while others seem so new, they might squeak. Some riders are lean, others less so. For those without their own bike, it’s all good. At a Slow Roll, they’ll size you for one, and you can bet it will look new and be tuned up tight. If you’re underinflated, they fill you up. If your seat is too low, they raise it.

I spot Anthony Taylor, the founder of Slow Roll. We almost bro-hug but bump elbows instead. Everyone is masked up. Taylor and I talk for a bit inside the house, which is gutted and occupied by about 150 bicycles, boxes of parts, and gear. It seems impossible that Anthony and I have never met; our mothers are good friends from the city’s Cultural Wellness Center. On Facebook, we have 234 mutual friends. We both love cycling; we both love being outdoors. I meet his daughter; she answers all my questions about school with patience and poise. Anthony’s son introduces himself. He’s effervescent and sports impressive dreads and a gigantic smile. He asks me if I want to snowboard this winter. “You think I can do it?” I ask. “For sure,” he says with a confidence that makes me feel like I can. He follows that with, “Well, are you good with failure?”

The Slow Roll was meant to launch at 5 p.m., but this gathering has CPT (that’s what we call “colored people’s time,” which is dictated less by the clock than by when people show up) all over it. At 5:10, Taylor says he’s waiting for a few more people. At 5:30, Minneapolis City Council Vice President Andrea Jenkins speaks. She talks about George Floyd and the community and the plans for the future—plans in which Taylor will play a prominent role. At 5:38, Taylor takes the mic, reviews the rules of the road, and talks about the route. The Slow Roll launches at precisely 5:47 CPT.

In 1995, Taylor helped create the local chapter of the Major Taylor Bicycling Club, a group for Black cyclists named after cycling’s first Black world champion. Rides with the Major Taylor club average 18 to 25 mph, so Taylor (no relation to Major) started Slow Roll as an alternative. Speeds on a Slow Roll average between 7 and 10 mph, and it’s not unusual for 100 people to join—many getting on a bike for the first time in years.

“[THE OUTDOORS] ARE WHERE WE FIND REJUVENATION AND RENEWAL AND CHALLENGE, AND THOSE ARE THE SEEDS OF HUMANITY.”

Taylor is 61 years old and lean, with muscles as defined as words in the Webster dictionary. In addition to cycling, he’s a devoted cross-country skier; he camps and paddles and snowboards with his children. In these activities, he almost always includes members of the Black community. “My instinct is to build community,” he says. Last winter, he took 56 Black people snowboarding. He also co-founded Cool Meets Cause, a program that introduces underrepresented, BIPOC youths from lower-income Minneapolis communities to snowboarding. But Taylor takes time to himself, too. Sometimes, on weekends, he rides his bike to Wisconsin and back—90 miles round trip. When I ask how he feels when he’s riding, Taylor replies: “I feel gratitude, immediately, of mobility, of healthy choices, of opportunity, and privilege. I realize riding my bike is a statement of revolution and liberation.” The lines between all this outdoor activity and his professional life are intentionally blurry. He’s a commissioner on the influential Metropolitan Council, a regional policy and planning agency responsible for economic development in the Twin Cities. After George Floyd was killed, Taylor began consulting with the YMCA of the North on racial equity in its outdoor programming, working with it to better serve communities of color. He was already consulting with the Sanneh Foundation, founded by retired professional soccer player Tony Sanneh, a St. Paul native and one of the Twin Cities’ Black pioneers in urban youth development. With Sanneh, Taylor helps provide fresh food to those who would otherwise go without it.

Taylor says he’s “trying to mobilize and have a real impact on quality of life for [affected] communities.” Moving the needle, collectively, means operating on a lot of different stages: it’s parks, it’s outdoors, it’s bike rides, it’s food. As part of that effort, Taylor convinced Ramsey County to help 20 youths gain certifications in mountain biking, paddling, cross-country skiing, and snowboarding. These kids will be paid to train, then teach these skills to others in their communities. Taylor argues that Black people will find it easier to learn if their teachers look like them. The main goal is to get them back to nature. “Our well-being is integral to how we connect to the outdoors,” Taylor says. A mile and a half south of where we launched, the Slow Roll stops at a simple one-story white house at 46th and Columbus, a house you might roll right past if you didn’t know it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014. On the northeast corner of the house’s lot, there is a sign labeled “South Minneapolis History: The Arthur and Edith Lee Family.”

The Lee family acquired this house in 1931 and persevered while white neighbors waged a cruel campaign to drive them out. No other Black families managed to move into the neighborhood for 30 years. There’s a steel plate etched with an image of Arthur Lee and a quote: “Nobody asked me to move out when I was in France fighting in mud and water for this country. I came out here to make this house my home. I have a right to establish a home. Arthur Lee July 16, 1931.”

Taylor’s voice is amplified by a speaker mounted to his bicycle. “A Black postal worker had white colleagues buy the house in his stead. He signed the paperwork and his wife did, and when they showed up as a Black family, there were riots,” Taylor explains. He adds that the Lees were protected in their home by fellow postal workers.

As our annus horribilis progresses, Taylor’s work in the Minneapolis community has taken on more urgency and imbued his outdoor advocacy with a missionary zeal. He’s kept the Slow Rolls rolling, beginning each one with intentional messaging around what Black people have lost, how we’ve lost things before, how we responded, how resilient we are. Taylor wants to “help all people realize the outdoors as a strategy for achieving the outcomes in humanity that we want. It’s where we find rejuvenation and renewal and challenge, and those are the seeds of humanity. Those are the seeds of what we want for our children.”

Cars take us in as they drive around us. It’s clear from their expressions that the drivers are seeing something they don’t usually see—a community ride, mostly Black, diverse in age and gender, taking its time. As a group, we also take up space. If the light changes while we’re rolling through, we keep going. We stay together. There’s music and chatter and laughter throughout. A sense of belonging arrives, followed by a sense of joy.

The Slow Roll returns to the building where it began. This was meant to be a hub for Taylor’s bike-related efforts, but he has different plans for the site now: It’s going to be called Dreamland on 38th. Dreamland refers to a Black-owned restaurant called Dreamland Café, which opened in 1937 as the first integrated restaurant in Minnesota. Dreamland on 38th will be a focal point of what will become the George Floyd Memorial District, running west from 38th and Chicago, where Floyd was killed, through Dreamland on 38th, continuing to I-35W, the highway that divided the haves from the have-nots when it was installed in the 1960s. Dreamland on 38th will be an incubator for Black entrepreneurs, and the planned district an international destination for people engaged in social justice.

Taylor has a plan, but he isn’t a vision guy in the way that vision guys dream big and pass the implementation on to others. Taylor is a doer, too. The plan is set. Policymakers are engaged. The funding is underway. An entire community is with him. Taylor is the ultimate multitasker; he does a lot of things. Dreamland on 38th will be one of them. Consider it done. — Michael Kleber-Diggs

Sean Sherman

Planting Native Roots for Local Needs in Minneapolis

Chef Sean Sherman was having a strange year even before much of his neighborhood burned. America’s foremost champion of native foods was set to cut the ribbon on a nonprofit restaurant in Minneapolis in 2020, but COVID had other plans. Then came the protests that took down the blocks around his kitchen at the end of May.

“Every building around us burned down to the ground,” says Sherman. “We were in martial law, basically. There was so much tension, so much paranoia, so much anger.”

So, what was a chef to do? Fire the burners back up and start feeding the neighbors, of course. “We mobilized our kitchen and got going, and we’ve been pushing out 200 to 400 meals every single day to our Minneapolis community, just to help with the food insecurity we’re seeing,” says Sherman. The program is in partnership with Second Harvest Heartland, is based on José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen NGO, and relies on the work of culinary experts who might otherwise be out of a job.

And while the plates underneath Sherman’s fare might be plastic rather than porcelain of late, his goal hasn’t shifted. For years, the chef has been on a mission to build interest in native cuisine—made from healthy “pre-colonial” ingredients, and free from processed foods, wheat, and dairy. The emergency meals Sherman and crew are doling out feature ingredients like scratch-made hominy, in-season vegetables, berry sauces, greens, and indigenous proteins like turkey, duck, or bison. The fare is not entirely dissimilar from one of Sherman’s pre-COVID catered dinners, except his team might be delivering it to a homeless encampment, or an elderly center. “It was kind of an experiment to see what would happen if we just pushed out this healthy indigenous food constantly,” says Sherman. “As the summer went on, they’ve become very popular. People are like, ‘I’ll take, like, four of those.’ ”

Not that “The Sioux Chef” should be surprised. In the handful of years prior to this COVID diversion, Sherman’s career took flight. His cookbook The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, which weaves recipes with personal narrative, some of it from his youth growing up on the Pine Ridge Oglala Lakota reservation, netted him a James Beard award in 2018. A year later, Sherman won another Beard, this time for leadership.

THE FARE IS NOT ENTIRELY

DISSIMILAR FROM ONE OF

SHERMAN’S PRE-COVID CATERED DINNERS, EXCEPT HIS TEAM MIGHT BE DELIVERING IT TO A HOMELESS ENCAMPMENT.

“He’s done this remarkable thing of sharing knowledge that’s somewhat ancient and vital, and might just improve the American way of looking at food,” says Alex Roberts, chef/owner of the longtime Minneapolis fine dining spot Alma. Roberts points to Sherman’s combination of heirloom versions of foods most chefs might overlook—corn, beans, chili peppers—paired with novel (but ancient) methods, such as using rose hips instead of non-native lemons as an acid.

Sherman’s experimentation extends beyond recipes to a varied slate of upcoming projects: a book, a podcast, plus a new restaurant set to open in 2021, downtown near St. Anthony Falls, close to a sacred site for native tribes.

But for now, Sherman is feeding the neighbors. And while “local foods” have become something of a cliché, Sherman’s hyper-focused approach—and his love for his city—seems to give the term a new relevance.

“People might look down upon everything that happened in Minneapolis this summer,” says Sherman, “but I feel like the city is really taking some big steps on trying to become a better community.” — Jesse Will

Matt Dumba

Putting Change at Center Ice

For Minnesota Wild defenseman Matt Dumba, the killing of George Floyd hit close to home—he lives just three miles north of the murder site in downtown Minneapolis. Lake Street, a main artery through the city that pulses with dozens of businesses owned by people of color, was hit particularly hard in the weeks that followed. Fringe actors from extremist groups targeted the neighborhood, fomenting violence that left several blocks devastated by arson.

At the time, Dumba felt helpless. He was quarantined with his teammates within the NHL’s Western Conference bubble, in Edmonton, Alberta, watching his city burn from over a thousand miles away. But the flames in Minneapolis sparked something within him.

Though far from home, Dumba was just a few hundred miles from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. There, his maternal grandmother, Edna Hanson, “a little old English lady,” as he describes her, had one son, Dumba’s Uncle Bob, then adopted seven children of different races and ethnicities, including a Filipino girl, Dumba’s mother, Treena.

“I have Black Jamaican cousins. I have Chinese cousins. I have First Nations cousins—I can’t see any of them going through this stuff,” Dumba says, refusing to allow them to be victims of racism and police violence. “I’m fighting for my family.”

In the weeks that followed, Dumba and his brother Kyle started Rebuild Minnesota, specifically to help the Lake Street neighborhood recover. Dumba personally committed $100,000 to the cause. Matt and Kyle’s efforts have inspired the NHL and the Wild to contribute another $100,000. They’re also encouraging community members to give. Those funds will help recover businesses, return jobs, and rebuild the most vibrant community in Minneapolis.

When confronting the work ahead, Dumba mentions the NHL’s dual Eastern and Western conference bubbles as similar to the insular communities that so many Americans have created. “The people in Minneapolis are great. I’m not taking anything away from them, but there are so many people in the suburbs that don’t have to deal with some of the stuff that’s going on right in the community,” he says. “It’s easy to fall into being in their bubble and just be comfy within it.”

With Rebuild Minnesota, Dumba was just getting started emerging from his bubble.

Coming up through the youth hockey ranks, he experienced more than a few racially motivated incidents. While Dumba’s teammates treated him well, opposing players—who couldn’t figure out his racial background—hurled every epithet in the book at him. He felt excluded at times. He had to work to see his role in a sport that is predominantly white.

Now as a role model for other minority players, Dumba knows that representation means more than visibility. He talks with young players about their experiences with racism on and off the ice. “Some of these kids are so demoralized,” he says. “It’s sad, and it bothered me for so long. I always wanted to listen and hear stories and share with them mine as well. I want to let them know they’re going through something someone else has gone through. Hopefully they can find strength in that.”

To that end, in June, Dumba launched the Hockey Diversity Alliance with eight other current and former NHL players. The HDA’s goal is to “eradicate systemic racism and intolerance in hockey…[and] inspire a new and diverse generation of hockey players and fans.”

With Rebuild Minnesota, Dumba’s making changes locally. With HDA, he’s changing professional hockey from within. And, in August, he used momentum from both efforts to propel him into the biggest spotlight yet.

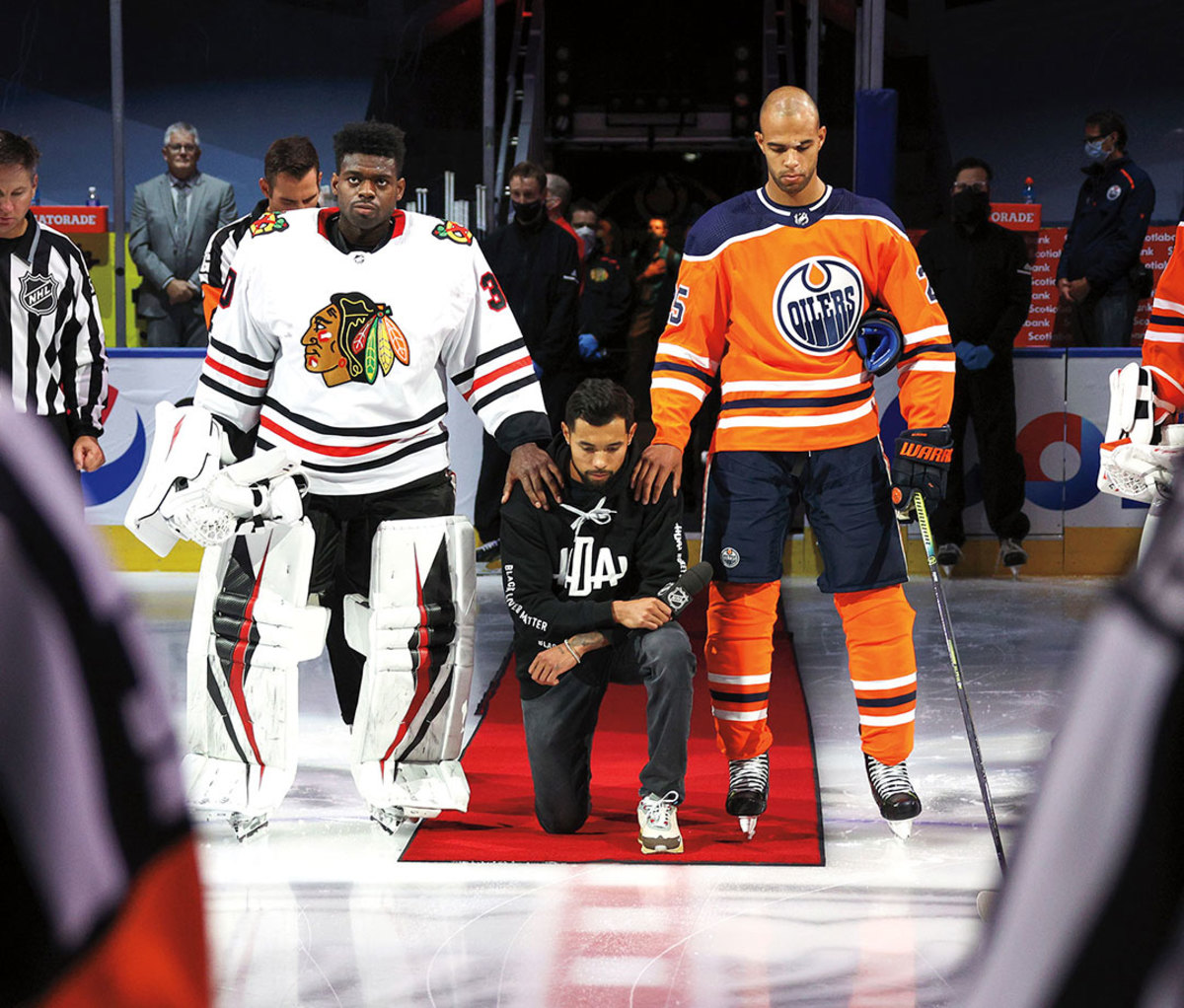

To kick off the NHL postseason, Dumba walked to center ice prior to the Chicago Blackhawks and Edmonton Oilers’ first playoff game. Wearing a black HDA hoodie, flanked by both teams, he took a deep breath and spoke haltingly but openly about systemic racism and his first-hand experience confronting the “unexplainable and difficult challenges” he faced solely due to the color of his skin.

“Racism is a man-made creation,” he said, “and all it does is deteriorate from our collective prosperity.”

Some words, even spoken quietly, can echo for years, and Dumba’s confident that the city of Minneapolis heard him loud and clear. “I hope all the talk progresses into action and people really step up,” he says. “People need to have those difficult conversations. They need to get out of their bubbles and be more empathetic.”

After a recent visit to the site of Floyd’s death, he notes the different energy there: “When you take the time to see the devastation in the community, it’s sad. But it’s also empowering, seeing the community come together.” — Michael Kleber-Diggs

Chris Montana

Distilling Hope

In the bleak times of the early pandemic, hearing about the desperation in his south Minneapolis neighborhood, Chris Montana set up a makeshift food bank from the warehouse of his distillery, Du Nord Craft Spirits. When George Floyd was killed by the police less than two miles from Du Nord and protests erupted, Montana set up a tent near the police department’s ill-fated Third Precinct building and handed out sanitizer he had retrofitted his business to produce.

Most of the protests were peaceful, but a small faction began trashing and looting the area surrounding Du Nord. Stores were broken into, cars were burned, and a deep unease overtook the community—including Montana, who grew up in the same neighborhood, along Lake Street. By the fourth night of protests, Montana received the phone alert that he’d been dreading, and also half-expecting: the triggered sprinkler system at the distillery. His business was on fire—years of hard work literally going up in flames. At 3 a.m., with an after-dark curfew in place, all he could do was sit and wait anxiously until daybreak.

“I’m a large Black man,” says Montana, “so the last thing I’m going to do is drive out and take on the National Guard.”

At dawn, he finally arrived to a few small fires still burning. Miraculously, the building was intact, even if entirely scorched and flooded by the sprinkler system.

Confronted with the destruction, his first instinct was simply to cry. The cost to fix the damage to Du Nord was extensive enough that Montana figured he’d have to pull the plug on his dream—again.

Montana didn’t expect the first blow that 2020 dealt. The year began on an upswing, with his distillery finally turning a decent profit. He’d started Du Nord seven years prior, after quitting his job as a corporate lawyer, managing it with his wife, Shannelle, and distilling his first batches of liquor from corn harvested from his father-in-law’s farm in southern Minnesota. “Up until this year, I think I paid myself a few thousand bucks,” says Montana, who also served two years as president of the American Craft Spirits Association. “This was the first year everything was coming together.”

When the pandemic hit, Montana closed Du Nord’s tasting room and was prepared to shut down the whole enterprise until, almost on a whim, he decided to use the clear liquor on hand to make hand sanitizer and give it away for free. He quickly saw the need for it firsthand, and scaled up.

“It not only allowed us to survive,” he says, “it allowed me to hire back all of the bartenders that I had laid off and give them hazard pay. They went from making 10 bucks an hour to 25.”

With the converted distillery restaffed and a food bank operating out of his warehouse, Montana was moving forward once more, right up until the fire. This second fallout, from the destruction of the protests—not a riot, Montana is quick to clarify—he could at least rationalize.

“It was an uprising from people who have been denied the basic right to citizenship,” he says. “I don’t condone any of it, but I absolutely understand it. It’s not just George Floyd getting killed. It’s the fog that exists over your entire life knowing that you could be George Floyd. That leads to frustration and anger. It has to have an outlet.”

Montana kept the food bank running out of areas in the building that weren’t burned. Donations poured in. He started a GoFundMe campaign and almost overnight it reached nearly a million dollars—11,000 people donated—so he set up a nonprofit. The Du Nord Foundation helps the food bank continue to feed 400 families a day, and lets Montana turn his sights to other businesses affected in his neighborhood.

“We lost 30 years of progress, and a lot of the businesses were Latino-owned. They lost damn-near everything,” says Montana, explaining the foundation’s larger vision to create a concentrated district along the Lake Street corridor with BIPOC-owned businesses who also own their buildings. “We’re hoping to buy up some property to get incubation spaces for these businesses.”

When he launched his own business, Montana had no idea it was the first Black-owned micro-distillery in America; it wasn’t that big of a deal or something he actively marketed. “I just wanted to make good booze, and that was it,” he says. Though he’s still determined to get the distillery going once again, he now sees a larger role ahead for Du Nord.

“Now, I don’t think we have the luxury of being in the background. We have to step forward, and we have to be louder.” — Ryan Krogh

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/38kcTzM

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment